I slip on my untied shoes and open the door. It’s a cloudless Saturday morning in Tijuana. The clean blue sky beams the muffled sounds of a nearby loudspeaker. The community soccer court a few houses down the road is full of white tents and red-shirted organizers. It’s election time.

I walk down the cement steps to the kitchen. “Quieres almorzar? Do you want breakfast?” my mother-in-law asks. “Si, gracias” I reply. Two eggs over-easy, cebollitas (sauteed onions), beans, corn tortillas and chile. “Estuvo muy rico como siempre, It was very good as always” I tell her. She takes my plate with a small but satisfied smile.

Leaning over the bathroom sink, I lift my t-shirt collar and dry my face. It’s been a week since I shaved. I pull a clean pair of socks from my bag to replace the ones I slept in. Shoes laced and camera bag on my shoulder, I head outside.

The streets are lined with cars. The mayor is on his way. The previous mayor, Jorge Hank Rhon, made a visit the year before to inaugurate the soccer court his government helped build.

|

This morning, residents from the working-class neighborhood receive free haircuts, medical screenings, and groceries. A man plunges a syringe into the thigh of a small dog. He cries out from the sting of the free vaccine and hobbles away. A young girl scoops him up, cradling her wounded little friend. The amplified voices of the organizers raffle off food, plants and toys.

A girl approaches, maybe 20 years old, speaking to me through sunglasses. She asks who I’m with. “Vengo de la colonia para ver qué onda, I’m coming from the neighborhood, to see what’s up” I say, trying to downplay the fact that I’m clearly not from the neighborhood. She asks me who I work for, and I tell her. A public media organization in San Diego, visiting family nearby, thought I’d see what all the fuss is about. She tells me she’s a communication major. I give her one of the cards from my bag. “Estamos en contacto, We’ll be in touch,” she says walking away.

From the improvised stage, they inform the crowd that the mayor’s visit is cancelled. They explain that he had an urgent appointment with the governor and offers his sincerest apologies. But not without further adieu. They announce the distribution of the despensas, essential groceries, and diapers. The crowd exits the soccer court and forms a line at the back of a worn palette truck. Those at the back of the line urge those at the front not to mob the truck, “Respeta la fila! Respect the line!”

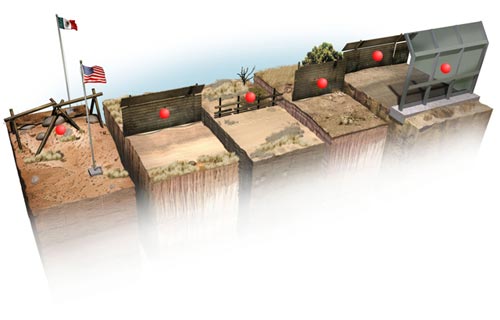

An hour later, the court is empty. The cars are gone. But the names of PRI party candidates Jorge Hank Rhon (running for governer of Baja California) and Jorge Aztiazarán (running for mayor of Tijuana) remain. Their signature red remains. The soccer court was strategically painted red. Hank had a large section of the border fence between San Ysidro and the beach painted red. The PRI is known for going into poor neighborhoods and giving free services. The people benefit from it. And so do the candidates.

Later that afternoon, my three nephews, my brother-in-law Fermin and I walk to the same red court for a game. They avoided the scene earlier, not wanting haircuts. “Lo cortan bien chueco, They cut it all crooked.”Fermin and I take opposite sides, and the boys split up. “Jugamos a soda, Loser buys soda.” After the game, they buy a two-liter of grapefruit Fresca and ask for 5 plastic bags. They fill the bags and pass them around. A quick twist to close the top and a tear out of the corner, it’s a refreshing victory.